|

| from: http://www.fao.org/zhc/detail-events/en/c/233765/ |

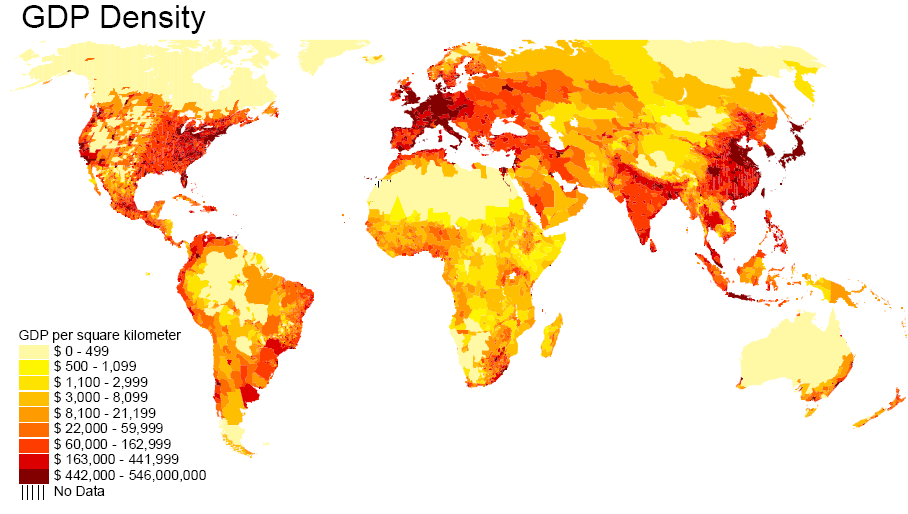

The ocean is

beneficial for societal wealth and human development. The oceans

offer access to food, materials, energy, and recreational

opportunities. Many states take (and took) initiatives to master

their access to marine resources; now often under a “blue”

catch-word [a]: “The

'Blue Economy' concept has attracted much interest in international

fora and become a key to development strategies of international

organizations. This cross-cutting initiative aims to provide global,

regional and national impact to increase food security, improve

nutrition, reduce poverty of coastal and riparian communities and

support sustainable management of aquatic resources.”

It is likely that

seas and oceans, even more than today, will be a theatre of competing

economic interests. Already today, the convenient availability of

ocean resources has put high pressures on the health of the ocean,

e.g.: overfishing shifts balances of ecosystems, pollution trough

extraction industries threats regional seas, marine litter spoils

recreation, plastic threatens marine life along the entire food

chain, or alterations of coastal zones destroy unique habitats. The

risk is high that these pressures increase when more “blue economy

strategies” get implemented. In that context, an index to describe

the overall ‘health of the ocean’ in a standardized manner would

be much needed and could be a very useful management tool.

|

from: http://www.oceanhealthindex.org/

News/Top_10_Clean_Water_Countries |

Drawing on

experiences in coastal zone management, comprehensive assessments are

emerging, which consider a composite of oceanic features that

influence societal wealth and human development. The

wealth of marine information that is available nowadays through a

multitude of studies may be incomplete, but a tentative assessment of

global ocean-health issues is possible. Against

this backdrop, proposing comprehensive ocean-health index [1] and

making it available [b] was a very important step forward towards a

sustainable human use of the ocean; although some may consider this

step as “bold” or even “too bold”.

Ten

amalgamated assets

The ocean-health

index amalgamates ten societal assets [c] undertaking one composite

assessment of reference values, current status and future status. The

ten assets were selected to cover a wide range of ecological, social,

and economic benefits for a wide range of “use cases”. The score

of the ocean-health index, a single number, shall describe the state

of the human-ocean system as a composite-asset. The main assumption,

implicit to the index, is that a combination of the ten assets should

be preserved for any healthy human-ocean system, although the

combination may vary regionally and in time.

The ocean-health

index is presented annually at country/regional level and at global

level. For 2012 and 2013, the score of the ocean-health index was

estimated to be a modest 65 of 100 when averaged at the global level.

The score of individuate countries varies between 41 and 94; and

countries of very different natural and economic setting have the

same score like Norway and Netherlands (74) compared to Iceland that

scores 58.

|

| from: http://medsea-project.eu/ |

The score for the

ocean-health index is calculated as the weighted arithmetical average

of the scores for the ten assets on which the index is built.

Selecting these assets, identifying indicators describing them,

gathering data measuring the indicators is a tedious and complex

undertaking, which in itself gives ample space for biases, nuanced

choices or simple errors. Improving the ocean-health index is subject

of research and study that, by no means, renders the index

meaningless, because it provides a means for global benchmarking and

comparison that otherwise would be missing.

Compared to

addressing possible defects “of substance” of the ocean-health

index, it seems ‘picky’ to question the use of a “weighted

arithmetical average” to calculate the score of the ocean-health

index. Nevertheless that was done recently [2], for very good

reasons, and with lessons that may serve as examples also for other

index that calculate a score for a set of assets.

An

innocent average ?

The mathematics

of a “weighted arithmetical average” that is used to calculate

the ocean-health index looks innocent and non-problematic.

|

from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/nhanes/

NHANESAnalyses/DescriptiveStatistics/Info3.htm |

An “arithmetical

average” of single marks gives each mark the same impact on the

composite mark. That makes good sense if a feature is marked several

times, a set of measurements, a sample, is obtained, and thus the

elements in the sample are belonging to the same kind but vary

randomly. Using weights is a simple and transparent approach to set

preferences between marks for features of similar kind, i.e. to

account for some non-random variation within a sample of “features

of about the same kind”.

Thus, in

face of the intrinsic complexity to assess in a composite context the

different assets that are underpinning the ocean-health index, taking

an approach of “one asset one vote”, i.e. arithmetical average,

looks like a fair, “democratic” first choice. Furthermore, giving

different assets different weights looks like a fair option to

reflect social or political choices without excluding a “minority

asset”. Nevertheless, just these simple first-hand choices are not

innocent but set a rather radical “normative frame” [2] for

managing a set of “assets” by means of a index, which may limit

the usefulness of the index.

Using an

“arithmetical average” to obtain a score for a set of assets

implies a paramount assumption, namely that “unlimited substitution

possibilities” exist among these assets to obtain the same score.

In that context, “substitution” means that under-performance for

one asset can be balanced by better-performance for another asset;

“unlimited” means that under-performance for one asset is not

limited by a lower boundary; and “possibility” means that

better-performance for any asset may balance under-performance of any

asset. These assumptions are quite radical, indeed.

Using a “weighted

arithmetical average” does not alter the assumption, although it

modifies the “cost” of the substitution; i.e. performance for an

asset with low weight has to improve much to balance a minor drop of

performance of an asset with a high weight.

A

radical “normative frame” ?

To perceive how

radical is the assumption of “unlimited substitution possibilities

among various assets”, one may assume: (1) a shopping list of ten

items for the dinner table, (2) getting these items in different

quality or quantity, but so that (3) the average quality of the

dinner is the same. Evidently, a good starter may make good for a bad

desert, or a good wine (or beer) compensates for…; but “unlimited

substitution possibilities among the various parts of the dinner”?

Common sense tells that this may work, indeed, but at best for a

“below-standard dinner”.

|

from: MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences

(distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu) |

Evidently,

“unlimited substitution possibilities among various assets” is a

framework for “a manager’s dream”. Such a framework maximises

the number of operational alternatives to amalgamate assets although

respecting social choices of different assets through their

weighting.

However,

“unlimited substitution possibilities among various assets” is an

exceptional case. It is ”the real-world’s manager’s headache”

that amalgamating assets is limited by the substitution potential

among them. The substitution potential may be limited for ecological,

technical or social preferences. Considering the ten single assets

that are amalgamated into the ocean-health index, it seems possible

that they substitute each other to some degree, but it is very

problematic management guidance to assume that they substitute each

other fully.

Strong

or weak sustainability ?

Extremes in

degree of substitution possibilities between assets is summarized in

two alternative concepts, of either “strong

sustainability”

or “weak

sustainability”.

The former requires keeping all assets above critical levels, thus

avoiding any substitution between them. Under the concept of “weak

sustainability” substitution

between assets is unconstrained and can be done without any limits.

That latter

concept of “unconstrained substitution” is applied for the

ocean-health index by the choice of the mathematical formulation how

the average score of the ocean-health index is calculated [2]; namely

using a weighted arithmetic mean.

The assumption,

which is implicit to the mathematics, namely “unconstrained or

unlimited substitution”, is unrealistic and may misled. However,

it goes without saying that experienced managers of marine resources

would be aware of limitations to substitution of assets, although

implementing that awareness for a set of assets in a competitive

environment is not only an intellectual challenge.

|

Border between open sea water and a plum

from the Mzymta river (Sochi, Russia)

from: Alexander Polukhin

(distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu) |

Obviously,

intermediate levels of substitution may be achieved for many

real-world situations and their description by means of an index. And

evidently, for many real-world situations it will be difficult to

determine “what are boundaries to substitution?” Manifestly, any

intermediate level of substitution for assets underpinning the

ocean-health index will depend on the specific ecological-human

intersections of the respective human-ocean system. Whatever is

obvious, evident or manifest, it will be hard and tedious work to

narrow the range of substitution possibilities, and in some

circumstances “strong

sustainability”

should be applied to guide management choices, simply.

The mathematics

to describe “intermediate levels of substitution” are available.

Likewise the tools are available to study implications of having

chosen a specific mathematical method to describe “intermediate

levels of substitution”. They are used, for example, in social

choice theory [d]. Aggregation of individual asset with constraint or

limited substitution into a composite scores can be described using

‘generalized

averages’ [e];

with arithmetic, geometric or harmonic average as special cases of

the ‘generalized

averages’.

Composite

averaging procedures and intermediate level of substitution

Choices of

limited substitution possibilities for the various assets of the

ocean-health index can be made [2] applying state of the art

knowledge on natural resources and ecosystem assessment, which are

reflecting the state of the human-ocean system, and using appropriate

mathematics, i.e. specific functional forms (“functions of

functions”) [f].

The mathematics

for calculating the index can get increasingly composite by working

in a nested manner, using generalized means, applying variable

setting of substitution with constraints on the overall score for the

less-performing assets, and fixing “hard” lower boundaries.

|

from: http://ecolutionist.com/the-new-ocean-health-index

-measures-human-impacts-on-our-oceans/ |

Evidently, such

kind of “composite averaging procedure” lacks the simplicity of

the arithmetical average. The “composite averaging procedure” is

more like an elaborated model of the substitution possibilities,

which has to be analysed with care; not only for his non-linear

behaviour.

Notwithstanding

the complexity, such a model could capture our best understanding of

the functioning of the ocean-human intersections though appropriate

mathematics. As such it may be a very useful research tool.

However, the

complexity of the model may be considered as much too high to abandon

the “weighted arithmetical average” because of its relative

transparency for many users. Thus for management environments the

“weighted arithmetical average” may be preferred.

Ocean-health

index with intermediate level of substitution

Recalculating the

ocean-heath index with a modified methodology to calculate the

average score [2], showed a considerable dependence of the

ocean-health index on the choices for the substitution possibilities

including substantial swings of countries between camps of

“well-performing countries” and “under-performing countries”.

|

The English Channel in Cap Blanc-Nez;

above the two ships a brown pollution layer;

probably containing NO2 and aerosols.

from: Alexis Merlaud (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu) |

The bulk result

of the study [2] is that the global ocean-health index decreases by

20%; namely from a score of 65 of 100 to the score of 52 of 100 if

the “weighted arithmetical average” is replaced by a revised

methodology limiting substitution among assets. The revised index

reduces less-realistic possibilities for offsetting poorer

performances in certain assets by better performances in other

assets. The drop of the global ocean-health index is important, and

possibly many decision makers, who would find a score of 65 of 100

“still tolerable” -

two good for one bad -, would

modify that view for a score of 52 of 100.

Even more

striking is the finding [2]:“...when

we turn to the assessment of individual countries. Countries with an

unbalanced performance across the assets significantly deteriorate in

the ranking compared to countries with a balanced performance. For

example, Russia and Greenland fall in the ranking for 2013 by about

107 and 118 places (out of 220) respectively, while Indonesia and

Peru improve by about 78 and 88 places respectively.”

Similar striking changes are observed regarding the assessment of

change over time, for one out of four countries the direction of

change is inverted.

What

is the lesson to draw?

Th ocean-health

index is useful because of the limitations of choices that were made

when designing it. The challenge to describe a set of assets through

a single index drives insights into the human-ecological

intersections of the human-ocean system, including the issue of

appropriate mathematical description.

A first

insight to keep:

Setting up an

ocean-health index [1] was a very relevant endeavour, and is a

lasting contribution to the management of the human-ocean system. An

ocean-health index could be a tool for comparison of national and

regional policies, benchmarking, and qualification of development

options, which is much needed to manage global commons like the

ocean. Implications of the (simple) mathematics to calculate the

ocean-health index have been analysed [2].

|

from: http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/

health/case_studies/plastics.html |

The result of the

study indicates that the mathematical method chosen for calculating

the average is causing bias of the index. The method to calculate the

score of the index by “weighted arithmetical average”, makes the

index insensitivity to less-appropriate choices to substitute assets

for which performance is low by better-performing assets. This

feature of the index limits the use of index. The possibility of

unconstrained mutual substitution between assets within the composite

score requires adjustment. Without such adjustment [2]: “policy

assessment and advice based on an index with unlimited substitution

possibilities could result in (a) certifying a healthy human-ocean

system for countries that in reality neglect important aspects of

ocean-health and (b) identifying development trajectories as

sustainable although this is actually not the case.”

A second

insight to keep:

The assessment of

the various oceanic features relevant for societal wealth and human

development is improved, if substitution possibilities among

different assets are constrained. Evidently, the substitution of

different assets is a societal endeavour. It requires knowledge,

social choices and norms and particular the latter may evolve and

vary among societies.

Nevertheless, any

substitution possibility should be limited and confined by boundaries

of the elasticity of the ocean system, if we know the ‘elasticity’

otherwise the “strong sustainability concept” or the

“precautionary principle” should be applied. For being practical,

the retained substitution possibilities should provide for some

elasticity to have a margin for management decisions -

not everything goes, not all is forbidden – to

render the ocean-health index a tool with operational value.

A third

insight to keep:

Furthering the

analysis of suitable substitution of assets and how to describe the

substitution process in mathematical terms is needed to properly

evaluate benefits, risks and development options of the ocean-human

system.

|

from: http://ocean.si.edu/blog/

penguin-health-equals-ocean-health |

For the best or

the worth, a common and robust ocean-health index is a much welcomed

management tool, and possibly the ocean-health index will be part of

any mature ‘blue economy strategy’. Thus, it is important to

design the index in a manner that is sound and practical. The

alternative would be to manage all assets one-by-one using the

“strong sustainability concept”, what possibly would end in a

political process to retain on a case-by-case only those assets that

are considered most relevant. In that situation any comparison of

national and regional policies, benchmarking, and qualification of

development options would be far more difficult.

Thus, one

composite index has a strong appeal. However, attention should be

given to the complexity of the averaging procedure, which if too

complex or perceived as too complex would hamper application of the

index. To recall, the attractiveness of calculating the ocean-health

index by a weighted arithmetical average is the simplicity of the

procedure that is understandable for many.

Possibly a two

tiers approach may provide a useful compromise. Tentatively, such a

compromise could be: (i) apply the “strong sustainability concept”

to identify assets that either match this concept or fail, (ii)

calculate the score of the ocean-health index for both subsets, (iii)

calculate the arithmetical average of both sub-scores (weighted by

the number of assets in each set) to get the score of the

ocean-health index, and (iv) present this score with the scores for

the sub-indexes as lower and upper bound.

Post

Scriptum:

How to generalize

this experience? What has been discussed above for the ocean-health

index applies "mutatis mutandis" to any index that gives an average

composite score of several assets that can substitute each other only

partially.

Ukko El'Hob

[c] The single

assets of the ocean-health index are: (1) Artisanal Fishing

Opportunities, (2) Biodiversity i.e. species and habitats, (3)

Coastal Protection, (4) Carbon Storage, (5) Clean Waters, (6) Food

Provision i.e. fisheries and aquaculture, (7) Coastal Livelihoods &

Coastal Economics, (8) Natural Products, (9) Sense of Place i.e.

iconic species’ and special places, and (10) Tourism &

Recreation [x].

[1]

An index to assess the health and benefits of the global ocean

(2012). Benjamin

S. Halpern, Catherine

Longo, Darren

Hardy, Karen

L. McLeod, Jameal

F. Samhouri, Steven

K. Katona, Kristin

Kleisner, Sarah

E. Lester, Jennifer

O’Leary, Marla

Ranelletti, Andrew

A. Rosenberg, Courtney

Scarborough, Elizabeth

R. Selig, Benjamin

D. Best, Daniel

R. Brumbaugh, F.

Stuart Chapin, Larry

B. Crowder, Kendra

L. Daly, Scott

C. Doney, Cristiane

Elfes, Michael

J. Fogarty, Steven

D. Gaines, Kelsey

I. Jacobsen, Leah

Bunce Karrer, Heather

M. Leslie et

al.,

Nature 488. doi:10.1038/nature11397

[2]

How healthy is the human-ocean system? (2014). Wilfried Rickels,

Martin F Quaas and Martin Visbeck. Environmental

Research Letters Vol. 9(4).

doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/4/044013